The gender divide in museum art acquisition

How does an artist’s gender relate to the acquisition and exhibition of art at the Harvard Art Museum?

Introduction

Fine art has historically been, like many other intellectual pursuits, a male-dominated field. But in the 21st century, graduation rates and occupational data indicate that women have finally achieved an equal level of educational access to fine arts fields: according to the National Museum of Women in Arts, women now make up 51% of visual artists in the United States. However, a comprehensive 2019 study of American museums by ArtnetNews revealed that the equality of entry into the fine arts field has not extended into an equal representation in art institutions. The study found that over the past decade only 11% of all acquisitions and 14% of exhibitions at 26 prominent U.S. museums were of works by female artists.

Using the ArtnetNews investigation as inspiration, in this article we explore the gender disparity in art represented at the Harvard Art Museum (HAM). Our guiding question was: “How does an artist’s gender relate to the acquisition and exhibition of art at the Harvard Art Museum?” Like ArtnetNews, we also looked at acquisitions and exhibition numbers of art from 2008 up to 2020 to get a glimpse into how our university’s art museum compares to those around the nation, with a hope to uncover how the representation of the work by female artists has changed over the past decade.

Gathering Our Data

Using the HAM’s public API, we searched the museum’s 250,000 object collection for all works purchased by the museum between 2008 and 2020. How a museum actually attains a piece of art can vary; some objects are gifted and some are purchased. We wanted to focus on HAM’s own proactive efforts to obtain art, so we only included objects purchased in our search. Within the record for each object, we extracted the year it was acquired, the year it was made, the artist’s gender, and the number of times it has been exhibited—this count includes exhibitions even before the formal acquisition of the piece. Based on the data in the API, for the purpose of our research a gender binary of male and female was assumed.

Findings

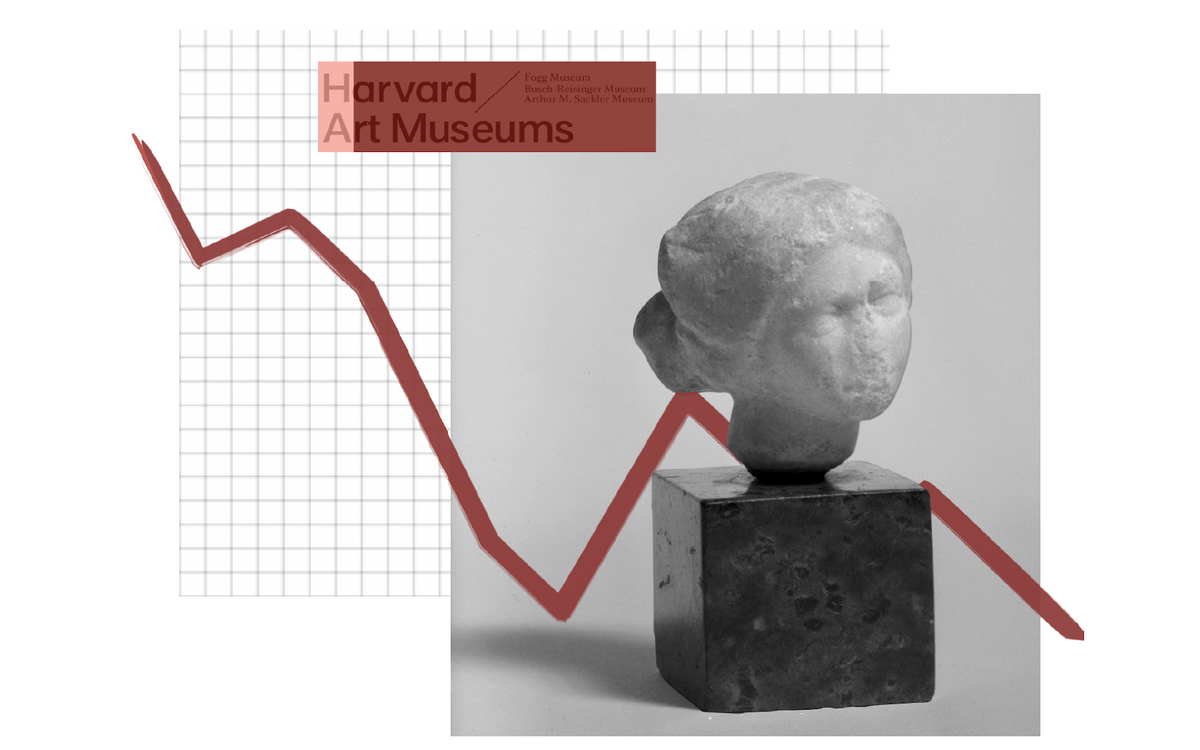

First, we determined the total gender breakdown of art acquired by HAM between 2008 and 2020. We discovered that of the 2,558 total purchases in this time frame, only 381 were purchases of work by female artists. This constitutes 15% of the overall purchases, which is slightly higher than the national average of 11% found in the ArtnetNews study.

Figure 1: HAM purchase of work by women vs. total purchases

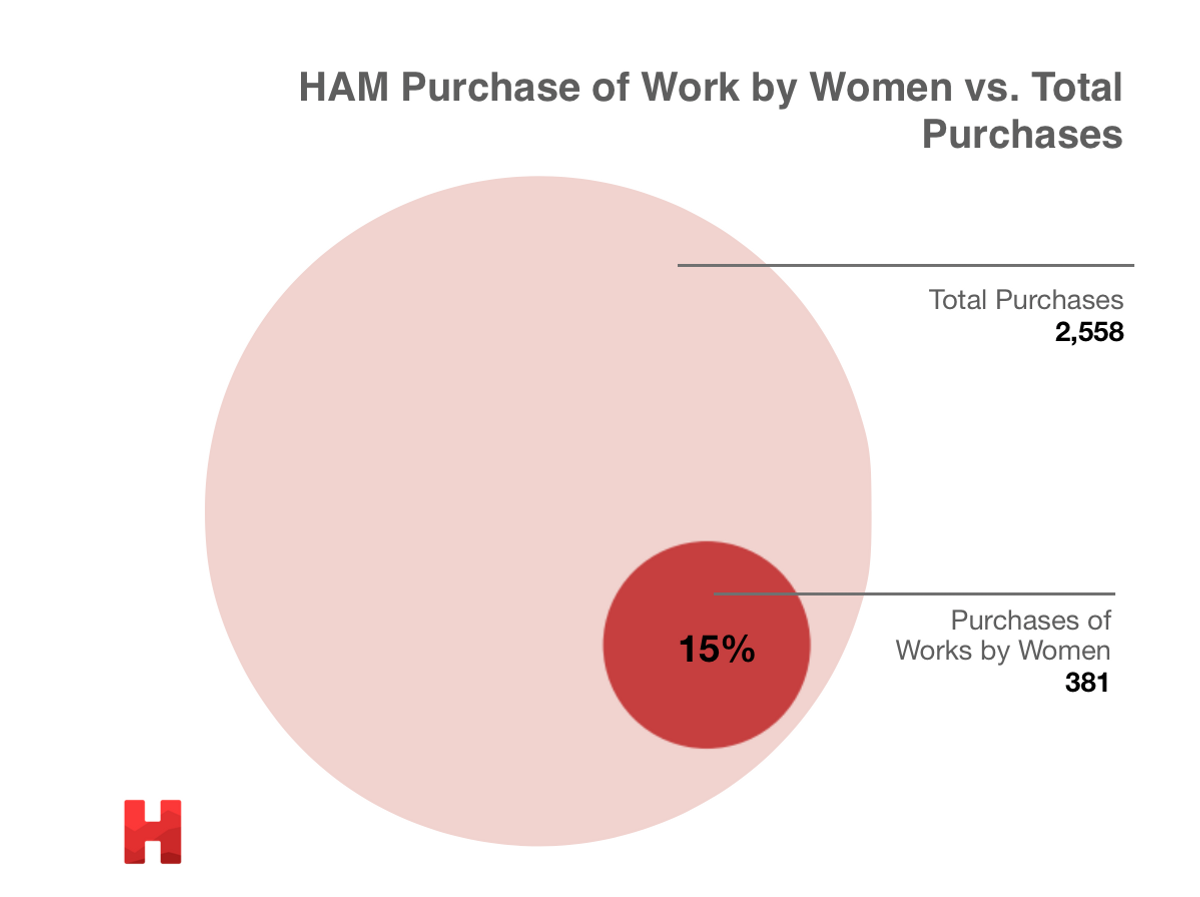

Figure 1: HAM purchase of work by women vs. total purchasesNext, we focused on any chronological trends that may have appeared over a little more than a decade. Our graph shows the percentage of female-created objects purchased every year from 2008 to 2020, with a high of 27% work purchased in 2010 and a low of 4% in 2017. There is not a clear trend to draw from in the graph, but an absence of an upward trend does indicate that Harvard Art Museum lacks a clear initiative to purchase from female artists.

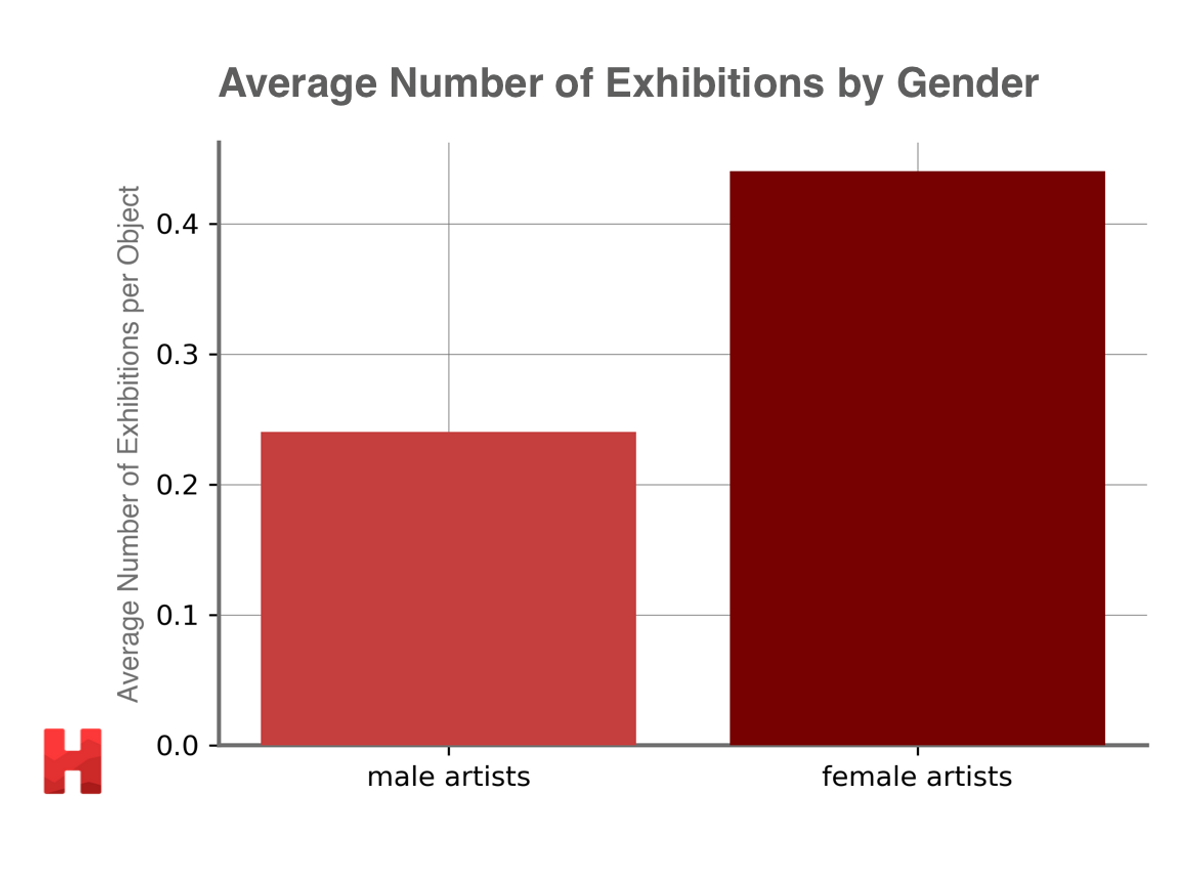

We then turned to exhibition numbers, or how many times the art has actually been displayed on public view. We wanted to see what the museum did with the objects after they purchased them, as only a small fraction of the HAM’s total collection can be on display at one time. In some cases, art was exhibited before it was formally acquired, so a number of objects have exhibition counts reflecting exhibitions whose actual dates fall outside our 2008-2020 date range.

One possible explanation for this is that the HAM could be repeatedly exhibiting female-created pieces in order to appear progressive. In other words, they have fewer objects made by women, so they display the ones they do have more frequently to escape censure for exhibiting male-only or male-dominated shows.

Figure 3: Average number of exhibitions by gender at the HAM

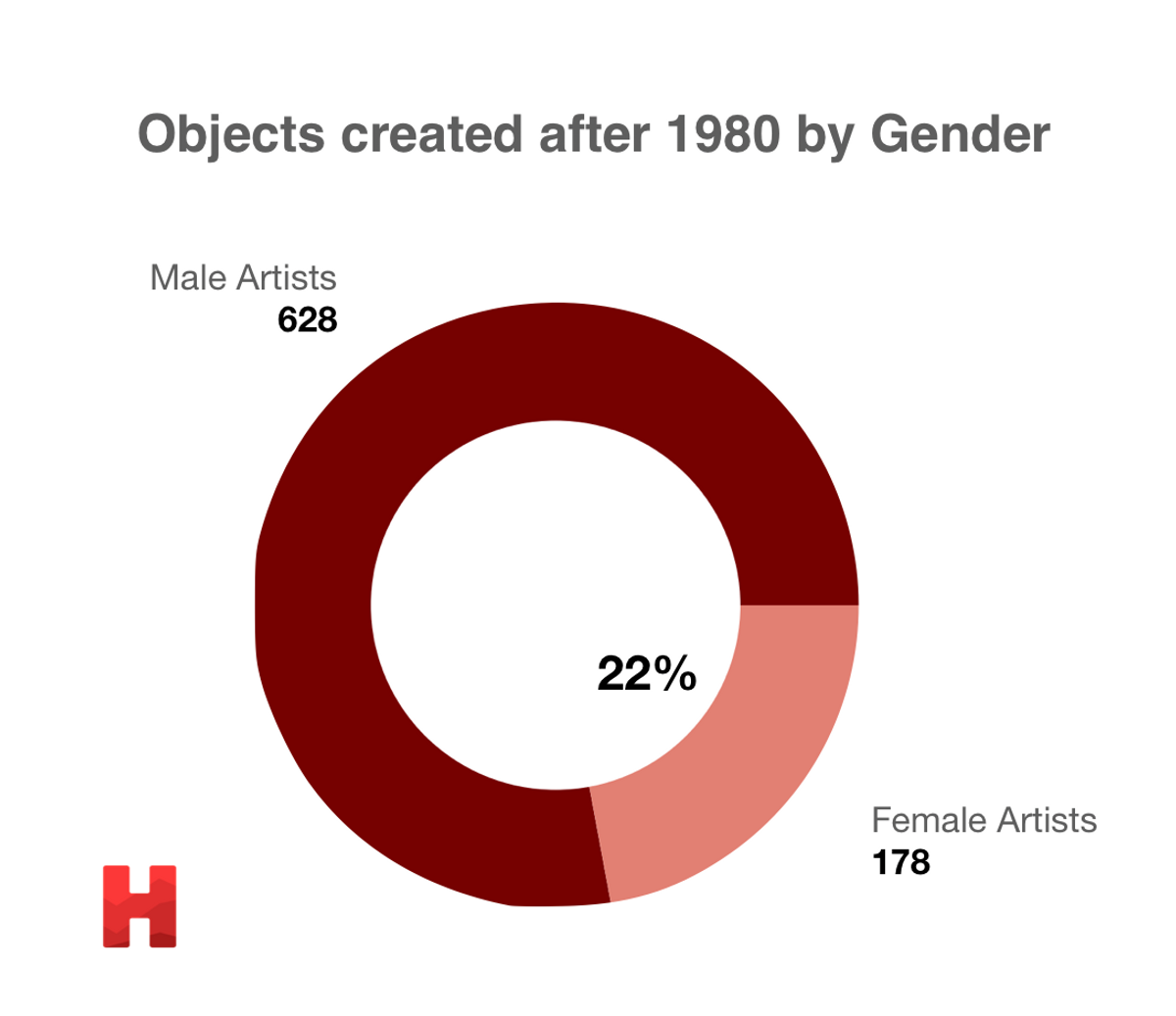

Figure 3: Average number of exhibitions by gender at the HAMFinally, we wanted to consider the gender breakdown controlling for “supply” of art. Historically, the vast majority of art that was made and then preserved was created by men, so it would be logical to think that the supply of objects available for the HAM to purchase would be mainly created by men. To control for this larger supply of male-created art in our analysis, we used data from this 2019 paper on the creation of professional art across the gender divide. The paper reported there was an increase in art-related occupations for both genders after the 1970s. The increase was higher for women at 226.0% compared to 82.6% for men. This finding was reaffirmed using a panel of more than 4000 graduates of the Yale School of Art (which is not only the oldest art school in the nation to grant professional degrees in art, but also one of the highest-ranked) as an indicator of visual arts graduation rates. When looking at classes from 1891 to 2014, researchers found that the gender ratio of Master of Fine Arts graduates equalized by the early 1980s.

Using the Yale study findings, we decided to limit our dataset to only objects created 1980 and later because, we reasoned, there should be a roughly equal supply of these objects as there was an equal number of male and female artists in the U.S. by then.

Figure 4: Objects created after 1980 by gender

Figure 4: Objects created after 1980 by genderIt is important to note that our data has its limitations: as mentioned, a number of the objects, particularly from the earliest centuries, do not have a listed gender for the artist. Based on historical access to the profession of artist, our default for these unknowns was “male.”

Conclusion

Our research identifying possible gender disparities in the acquisition and exhibition of art at the HAM showed that overall, the museum had trends similar to those at the national level; 15% of their acquisitions over the past twelve years are from identifiably female artists, as opposed to the national average of 11%. We also postulated that the lack of clear trend in the number of works acquired over the course of this period demonstrates a lack of commitment on the HAM’s part to increase purchases of female-created art. What art institutions purchase and display has a huge impact on the art and culture of our time, and on who gets to participate in the creation of that art. By withholding the financial and promotional benefits that come from being shown in a museum, museums like the HAM are feeding the cycle of omittance of female artists.

Overall, this provides an interesting perspective about how the art we interact with is also influenced by other factors such as gender. It also shows how important data analysis and communication can be in highlighting institutional inequalities. For further analysis, it could be worthwhile to explore if this gender disparity also appears in peer institutions to Harvard (such as the Yale University Art Gallery), or to expand analysis into other traditionally underrepresented groups (such as POC and the LGBTQ+ community) in the visual arts.