Why The Harvard Housing Lottery Might Not Be Random

Size matters, along with many other factors…

Since the start of the random lottery system that assigns Harvard freshmen to upperclassman Houses, Harvard College administrators have insisted that the process is indeed random. For years, though, students have speculated that this was not the case. The Harvard Open Data Project made it our mission to investigate.

Our first survey and analysis, posted here, asked freshmen in Harvard’s Class of 2020 their House preferences ahead of Housing Day on March 9. Our second survey, released after freshmen had been “sorted” into their House communities for the next three years, asked further demographic questions that we used to determine if there are any trends in House assignments.

Harvard’s “random” lottery resulted from a desire to make each house a microcosm of the university. In previous years, when given the choice, students chose to live with people who were exactly like them, which led to homogeneous groups connected by interests, religion, or socioeconomic status.

So which side is right? To answer, let’s look deeper into the data.

Football “luck”?

Harvard’s football team in action against Princeton in 2015 (Source)

Harvard’s football team in action against Princeton in 2015 (Source)There are 28 freshmen on the varsity football team. Not a single one of them was “quadded.”

There were two blocking groups of eight football players that linked and one group of seven. The remaining four football players blocked with non-football players. In total, there were seven blocking groups that had at least one football player in them. Of these seven blocking groups, not a single one of them was assigned a Quad House—Cabot, Currier, or Pforzheimer.

It is entirely possible that this was indeed a random result. But, for many students, this seems like more than simply a coincidence.

Quad: Pforzheimer, Cabot, Currier; River East: Dunster, Leverett, Mather; River Central: Adams, Lowell, Quincy; River West: Eliot, Kirkland, Winthrop.

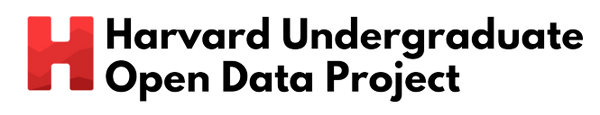

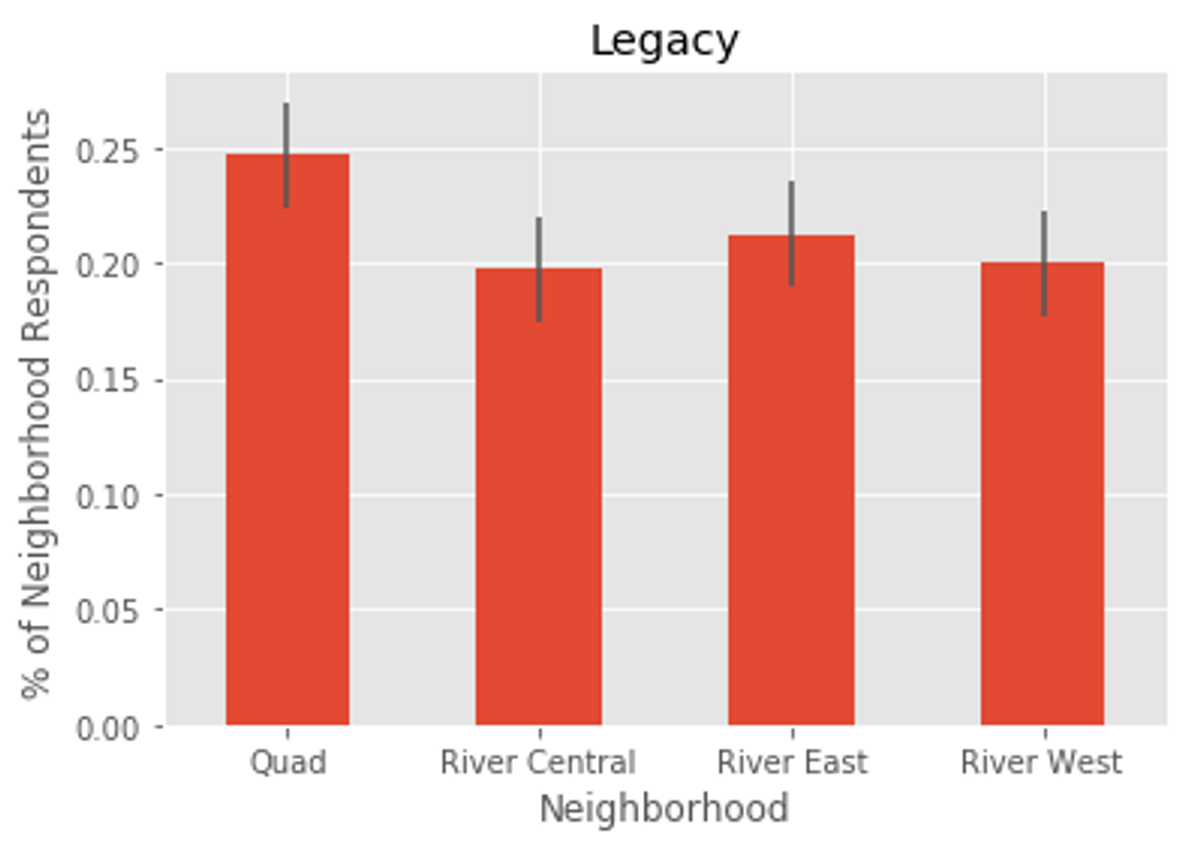

Quad: Pforzheimer, Cabot, Currier; River East: Dunster, Leverett, Mather; River Central: Adams, Lowell, Quincy; River West: Eliot, Kirkland, Winthrop.Note: In reading the above graphic and similar ones below, the red bars represent the proportion of respondents in each community who identified with the trait in question, while the black bars represent a standard deviation from each neighborhood’s measured proportion.

As a whole, however, 162 of 615 survey respondents (26.3%), reported being assigned to one of the three Quad houses. Compared to the subset of 19 0f 94 varsity athletes (20.2%) who reported being quadded, it appears as if these rumors may hold some weight. However, these data points are not statistically significant by themselves; further analysis of future Housing Day results would strengthen these findings.

Size Matters

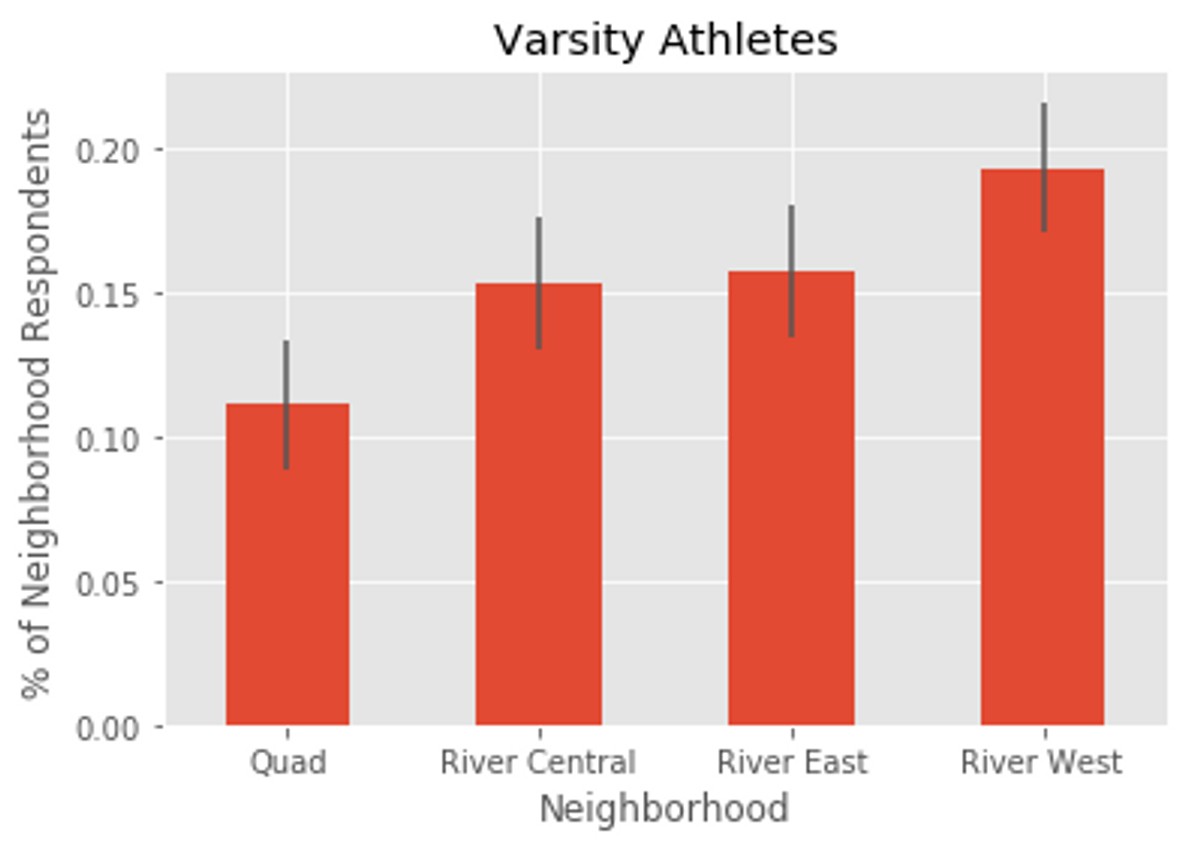

Blocking groups with eight people were much more likely to get quadded.

Blocking groups with eight people were much more likely to get quadded.As shown above, our survey results indicate that blocking groups of eight people are much more likely to be assigned to a Quad House than smaller blocking groups. These full blocking groups were twice as likely to be quadded than assigned to a House in the River Central neighborhood (Adams, Quincy, and Lowell).

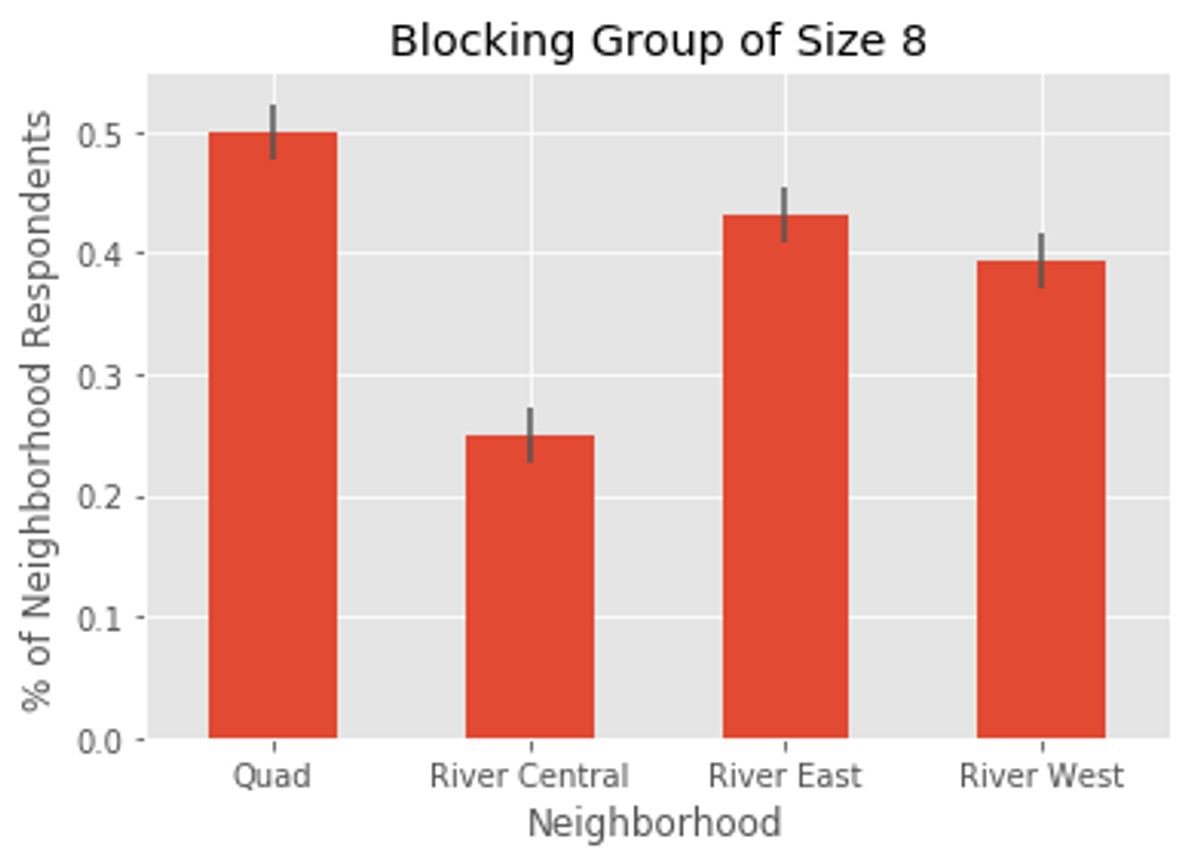

Large blocking groups that linked with other groups were more likely to get quadded.

Large blocking groups that linked with other groups were more likely to get quadded.Additionally, blocking groups that didn’t link with another group were far less likely to be quadded than placed in a River House. The smaller sizes of many River Houses may explain these trends; these Houses are unable to accommodate numerous large blocking and linking groups.

Just one year of data isn’t enough to be conclusive. But, if an enterprising freshman wants to avoid the Quad, they could do worse than choosing a small, un-linked blocking group.

The continued distaste for the Quad among freshmen defies logic, however, when considering that residents of Quad Houses generally have higher satisfaction with their Houses than those of River Houses, according to a 2015 survey conducted by The Harvard Crimson.

Blocking group size is a fairly easy metric to measure and change, but less malleable aspects of a group's identity may also play a significant part in where the group is assigned.

Legacy and other factors

It does not appear that having parents or siblings who preceded your Harvard journey affects House placement. We asked respondents who are legacies whether or not they were placed in the same House as their relative:

Only 16 of 132 legacy respondents (12%) responded having been assigned the same House as a relative. More interestingly, 19 respondents (14%) responded having multiple family members who lived in different Houses.

These results may put to bed rumors that Faculty Deans (previously known as House Masters) in each upperclassmen House have the ability to “select” freshmen of choice who may have legacies in a certain House.

We also considered other factors like race. While we asked about the race of respondents on our survey, the relatively few number of respondents in each House makes it difficult to determine any significant trends, as differences could be entirely a result of nonresponse bias.

A Dingman non-denial?

A Housing Day 2017 video released by campus group On Harvard Time features Dean of Freshmen Tom Dingman, who when asked whether House placements are truly random, responds:

Whether this means anything or not, is up to you to decide.

Other administrators claim randomness

After running the data, we spoke with Amy Vest of the Office of Student Life, the department that runs the housing lottery. She was very helpful and explained that, to her knowledge, the process is entirely random outside of a few small factors like accommodations for accessibility (since not all houses are accessible). We’re inclined to trust Ms. Vest, but as a matter of scientific principle we need to keep collecting and analyzing data to come to a definitive conclusion.

Interesting anecdotes

We can’t draw any conclusions from anecdotes, but we found a few House placements that were interesting, at the very least:

- Five of twelve students in “The Art and Craft of Acting,” a freshman seminar, were placed in Adams House. Adams has traditionally been a House known for its artsy vibes.

- Pforzheimer House welcomed its largest incoming class in recent history according to a House rep. Another member of the house noted, “given the ‘trade deficit,’ I suspect the Quad always needs disproportionately more people.” That said, a member of Cabot House reported that it welcomed “close to our lowest number ever.”

Conclusion: more data needed

While there may be some data and anecdotal accounts that support theories that the Housing lottery is not random, we believe that one year’s worth of data is not enough to definitively make this claim. We at the Harvard Open Data Project are committed to running this survey in future years to continue studying this Harvard mystery.

If you have interesting theories or anecdotes you’d like us to share or investigate further in future years, reach out to us!

Our raw data is available on GitHub — give it a look, and give us a shout if you find anything interesting!