How Do Harvard Students Feel About Their Housing?

As the summer draws to a close, college students across the country pack up their things and depart for their new homes. At Harvard, the class of 2021 has moved into their residential houses for the first time.

The Harvard Open Data Project has written extensively about Harvard’s housing system and whether students are placed randomly as the administration claims. Last March, we released an analysis of the housing preferences of the class of 2021, prior to housing day.

Shortly after first-years received their housing assignments last spring, we sent out a survey via email and offered Insomnia Cookies to those who filled it out. Our intent was to understand not only where students were placed, but also how they felt about their assignments. We received a record 507 responses, more than a quarter of the entire class.

It is important to remember that this data comes from a sample of the entire class, and is not necessarily representative.

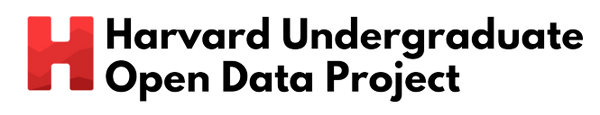

How Satisfied Were Students with Their Housing Assignments?

Incoming Winthrop, Lowell, and Dunster residents reported the top three highest levels of satisfaction. This is unsurprising; newly renovated houses and spacious swing accommodations remained the envy of many students. As is consistent with previous findings, those assigned to the quad reported the lowest levels of satisfaction with their assignments.

The Quad Lawn looks like a pretty nice place to live (Harvard YLC)

The Quad Lawn looks like a pretty nice place to live (Harvard YLC)Did Opinions of Houses Change?

How did the mean satisfaction rating per house differ before and after housing day?

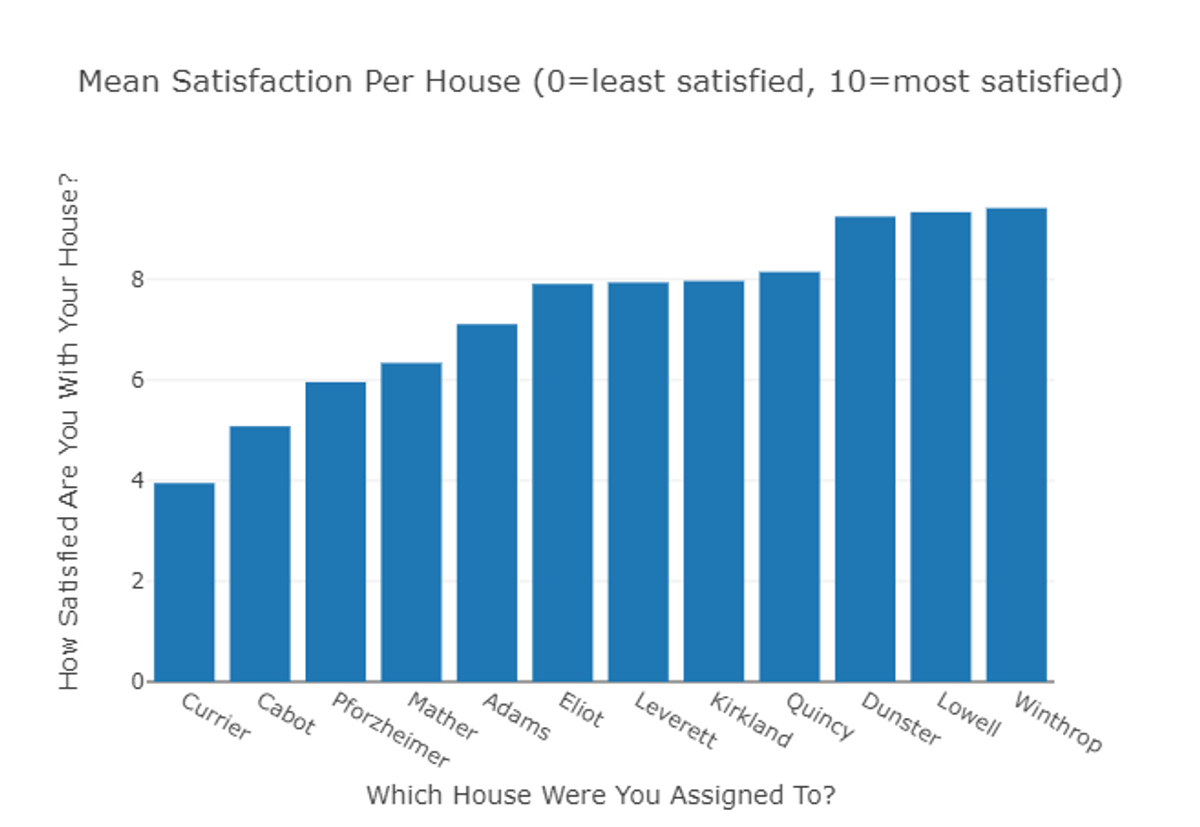

We asked students to rank all of the houses by desirability prior to receiving their housing assignment. Once the housing lottery had occurred, we asked respondents to rate their level of satisfaction with their new housing assignment. These measures were ranked against one another to allow for direct comparison. Since both of these surveys were anonymous, it is impossible to determine whether the same group of students who filled out the first responded to the second, so it is difficult to conclude that the following changes are due to changes in opinions of the houses and not simply a change in the sample.

Sentiments Toward Each House Stayed Largely Constant

Winthrop, Lowell, Dunster, and Quincy maintained their top four positions post-lottery. Cabot and Currier switched, still occupying the last two places, but this may be due more to the change in samples than a genuine change in sentiment.

Neighbors Eliot House and Kirkland House also traded places with one another, Eliot moving up two spots and Kirkland moving down two spots. The two houses are virtually identical in location, so it’s unlikely that this was a deciding factor or differentiator.

Note: It is possible that these results are insignificant due to a combination of chance, bias in the sample, and other factors.

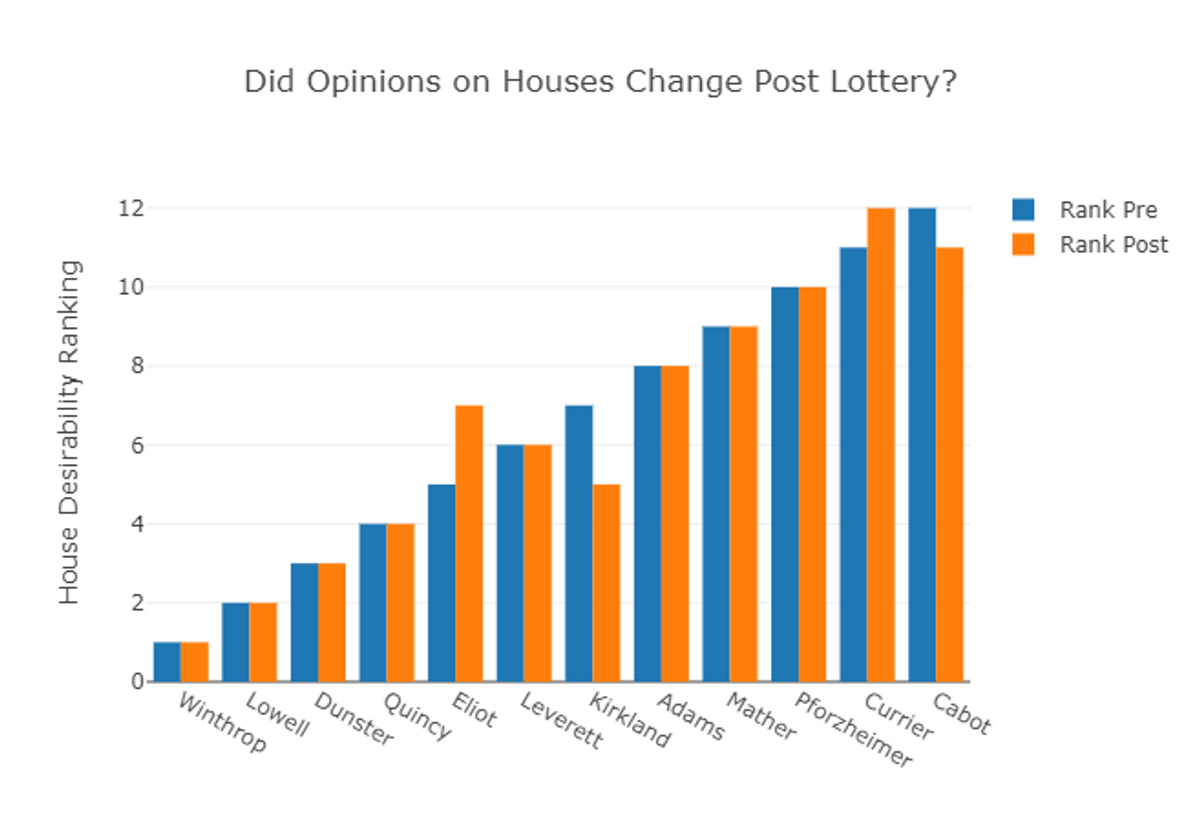

Do Blocking and Linking Group Size Matter?

Our 2017 analysis suggested that blocking groups with 8 members were twice as likely to be quadded than assigned to a House in the River Central neighborhood (Adams, Quincy, and Lowell).

Additionally, in 2017 we found that blocking groups that did not link with another group were far less likely to be quadded than placed in a River House.

Our 2018 results contradict many of our hypotheses from the year prior.

This year, only 23% of respondents who were members of blocking groups of 8 people were quadded, compared with 33% last year.

Contrary to last year’s results suggesting that linking would increase chances of being quadded, 75% of respondents who were assigned to Currier House did not link with another blocking group.

Although some trends emerged, we simply don’t have complete enough information to draw substantial conclusions. For example, we have no way of knowing if every single member of one blocking group filled out our survey, or if each response was unique to a different group.

Housing, like Harvard, is what you make of it.

The vast majority of upperclassmen report being very satisfied with their housing assignments. Adjusting to any new environment can be difficult. It might take a few weeks to successfully navigate the Adams tunnels, or to learn the names of the Kirkland dogs, but that’s okay.

Whatever your challenges may be, rest assured that your house will soon become a home.